|

|

|

What are the differences between “sci-fi, fantasy, and horror film music” and music from other film genres? The answers might surprise you. INSTRUMENTATION AND ORCHESTRATION WHAT MAKES MONSTER MUSIC SPECIAL?

THE STYLE OF “MONSTROUS” MUSIC The argument that science fiction and horror music “sounds” different from other film music can be easily disproved by the fact that the same cues have been used in both monster and non-monster movies. As fans of our Monstrous Movie Music series know, a lot of the music that is so indelibly linked to the monsters they love is, in fact, equally indelibly linked to other visuals as well. Herman Stein’s powerful “Main Title” (click on audio link) from Universal’s 1955 Tarantula perfectly conjures the menace of a colossal arachnid running loose in the desert. Except for one thing. The piece was originally written in 1952, where it served as the “Main Title” for Universal’s Rock Hudson western, The Lawless Breed. This process of “tracking” -- re-using cues from the studio’s music library in subsequent pictures -- shows that what makes something sound “monstrous” is often merely in the ear of the beholder. When that same Tarantula causes a landslide and John Agar returns to investigate the site, a spooky sci-fi motif plays on piano in a cue written by Henry Mancini. What inspired Mancini to come up with this piece that perfectly evokes the mysteriousness of the situation? The 1955 Dana Andrews/Piper Laurie western Smoke Signal, for which he originally wrote this Indian-inspired cue known as “Down River.” One final example from Tarantula occurs when the creepy critter approaches Professor Deemer’s house. This Herman Stein cue perfectly enhances this scary scene. But the cue’s title -- “Great Truck Robbery, Part 1” -- is a dead giveaway that it wasn’t written for this monster picture. This marvelous suspense cue was originally composed for Universal’s Tony Curtis crime drama Six Bridges To Cross. Universal-International wasn’t the only studio to re-use their non-monster cues in monster movies. Some of the music written for Warner Brothers’ The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms came from both Chain Lightning and the 1950 Robert Wise soap opera, Three Secrets, and that Bronislau Kaper’s score for that studio’s Them! had some music derived from the 1942 Tracy/Hepburn film, Keeper Of The Flame. The Main Title from Columbia’s Earth vs. The Flying Saucers was a slowed-down version of “Trial And Escape,” a Daniele Amfitheatrof cue written for that studio’s classic 1942 political comedy Talk Of The Town, starring Cary Grant, Jean Arthur, and Ronald Colman. More examples include Stravinsky's ballet music from “The Rite Of Spring,” which was later used to depict dinosaurs in Disney's Fantasia, “Also Sprach Zarathustra,” which is inextricably linked to 2001: A Space Odyssey, and some of Jerry Goldsmith's cues from Freud, which were re-used in Alien. Not only did western, crime, and political comedy music function perfectly well in monster movies. It also worked the other way around. Herman Stein’s classic sci-fi

cue “Visitors From Space,” from Universal’s It Came From Outer Space, later appeared in a life raft scene in the Jeff Chandler tearjerker Stranger In My Arms. Bits of music originally composed for The Deadly Mantis, This Island Earth, and The Monolith Monsters were all stitched together to become the Main Title of the 1961 western, Posse From Hell. The reason music from one movie genre can be successfully re-used in another is because there really isn't much of a difference between various “types” of film music. Divorced from the visual, it’s often impossible to guess what genre of film a particular cue was written for. While some film composers won’t admit it, a cue they’ve written for a specific situation might not work any better than music they’ve written for another sequence in a completely different picture. A chase in a film noir can often be inserted into a western chase or a horror chase and nobody would be any the wiser. Irving Gertz’s masterful “Eskimos Attacked” from The Deadly Mantis was later used when the dam is blown up in The Monolith Monsters, and after that it augmented a scene where a car speeds toward a caveman in Monster On The Campus. It’s not as difficult for music to “fit” a scene as you might think, because as different as these three action-filled visuals are, in the hands of a good piece of action music, they can all sound the same. Of course, not all cues can be re-used in any scene, even if the scenes are similar. If a musical cue had quirky instrumentation to it, like honking woodwinds resembling geese, chances are it wouldn't get used again unless the studio had a successful goose series. As beautiful a cue as Frederick Hollander’s “Heaven” is, it was rarely re-used by Columbia after it was composed for Here Comes Mr. Jordan, as its “celestial” feeling made it unsuitable for most of that studio’s pictures. One exception was when it was adapted as part of the Main Title for 20 Million Miles To Earth, to be heard on our forthcoming MIGHTY JOE YOUNG CD. Nothing Special About Musical Recycling It shouldn’t be surprising that studios re-used music from one genre to another, as music departments weren’t the only departments recycling preexisting material. In addition to the music libraries, studios had their own stock footage and sound effects libraries, and they re-used these same resources across a wide range of pictures. The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms opens with a great optical whirlpool effect, an effect that Warner Brothers had already used a number of previous times, including a flashback scene from their 1950 melodrama Three Secrets. Explosions in Universal’s Audie Murphy biography To Hell And Back looked suspiciously similar to ones the studio used in This Island Earth, because they were manufactured by the same special effects team. Republic’s gunshots and Warner Brothers’ thunder sound effects were recognizable no matter what genre of film they were used from, and some of the same stock footage and sound effects were used by more than one studio, as some source material was made available to more than one production outfit. |

||||||||

|

THE COMPOSERS OF MONSTROUS MUSIC There are many ways to score a science fiction or horror film, but the composer's writing style is the main factor in determining what the music will sound like. A Dimitri Tiomkin score sounds like Dimitri Tiomkin regardless of whether he wrote the music for a crime thriller or a fantasy. Bernard Herrmann always sounds like Bernard Herrmann, John Williams sounds like John Williams, and Hans Salter sounds like Hans Salter. Just like Mozart and Bach sound like Mozart and Bach. Tiomkin’s classic “sci-fi score” for The Thing more closely resembles his non-sci-fi scores like Fall Of The Roman Empire and Duel In The Sun than it resembles Bernard Herrmann’s sci-fi score for The Day The Earth Stood Still or Leith Stevens score for War Of The Worlds. No composers only scored horror films -- they scored every type of film that was assigned to them. Almost all film composers scored at least one monster, science fiction, or fantasy film, and for those few who didn’t, it was probably because they didn't get the opportunity rather than because they didn't want to. When a composer had to score a horror film, he didn’t learn a whole new way to compose in the few weeks he had to complete his assignment. Instead, he treated the picture with the same stylistic and dramatic tools he used in his other films. There’s no mistaking the fact that The Golden Voyage Of Sinbad’s score was written by the same Miklós Rózsa who composed the music for Ivanhoe and The Red House; Angelo Francesco Lavagnino’s monster movie Gorgo was clearly the product of the same composer who scored The Last Days Of Pompeii and The Naked Maja. It’s true that there’s a “sound” sometimes associated with “Grade Z” horror scores, but this is generally due to the fact that these scores were

written by “Grade Z” composers, or at least composers who weren’t as good as some other composers. But their horror scores sounded more like “Grade Z” mystery or “Grade

Z” adventure scores than they sounded like “Grade A” horror scores. [It should also be noted that many “Grade Z” scores were written for projects with almost no music budget

whatsoever, meaning the composer wouldn’t be able to hire as many musicians as he would have liked, he probably had less time to write the score, and very little time to record it.] As low-budget and as silly a film like The Mole People is, the score by Hans Salter, Heinz Roemheld, and Herman Stein could easily have accompanied a far more expensive and prestigious picture. Good composers generally write good music for all types of films, and bad composers generally write bad music regardless of the genre they’re writing for. Composers Acting Like Actors Composers were no different from the other personnel working on motion pictures. Even actors had a certain “style” that they used in every type of picture they starred in. In the 1950s, Universal-International had stars under contract like Tony Curtis, Piper Laurie, John Agar, Jeff Chandler, Charles Drake, and Julia Adams, many of whom appeared in their science fiction films as well as westerns, romances, swashbucklers, and every other genre imaginable. Warner Brothers had Humphrey Bogart, Errol Flynn, and Bette Davis. And like the composers who contributed their same compositional style for different types of films, the actors’ thespian style dictated their performances more than the film genres they were acting in. Had Errol Flynn appeared in a monster movie (thank goodness he didn’t!), he wouldn't have acted like Boris Karloff or Vincent Price -- he would have acted like Flynn. The same also applies to directors, producers, and technicians. |

||||||||

|

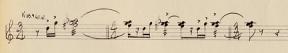

MONSTROUS INSTRUMENTATION Now that you’re convinced that there's absolutely no difference between science fiction/monster music and other genres of film music, here are some differences: Sometimes, electronic instruments were used, often played solo or in the foreground, helping to create an unearthly sound to lend an air of strangeness to the proceedings.

Novachord and Hammond Organ were both used for this purpose, but these keyboards were a staple of many studio orchestras, and they were used in almost all of their films. However, while they were sometimes

used to bolster the small string section of the orchestra, in science fiction films these instruments sometimes had a more prominent role. You can hear them throughout the Creature From The Black Lagoon series (listen to “Prologue” from the first Creature film) and This Island Earth.

These instruments were eventually replaced by modern-day synthesizers, which allowed for a wider range of musical and sound effects, but they often mimic their precursors in adding an appropriately mysterious

atmosphere to a film. The electric violin thankfully wasn’t popular for very long, because it could tend to drive people to madness if they were forced to listen to it for extended periods. This was partly because it was often played as a droning sound effect, something you can hear in many modern synth-dominated scores. Although there's no sound in outer space, you couldn't tell Hollywood that, because the electric violin often became the sound of space, as in It! The Terror From Beyond Space. Cut to a shot of outer space and it sounds like you've got ringing in your ears. The electric violin was used effectively and melodically by Irving Gertz in The Alligator People. The ultimate electronic instrument is the Theremin, which was used by Miklós Rózsa for films like Spellbound, The Lost Weekend, and The Red House. It's a box of electronics with two metal rods, one controlling pitch and the other volume, and it makes its weird sounds when your hands move near the rods. Rózsa used it to convey the abnormalities of the human psyche in these earlier films, so it was a short step for the Theremin to also be used for other abnormalities like monsters and space aliens, and it was used by Bernard Herrmann in The Day The Earth Stood Still, By Dimitri Tiomkin in The Thing, and by William Lava in Phantom From Space. The Theremin can be a very temperamental instrument, as it is difficult to play, and Universal was aware of this when they used it in It Came From Outer Space, recording the orchestra first, and later overdubbing the Theremin onto the orchestral tracks. Here’s what the “Main Title” sounds like in its finished form with Theremin, and what it would have sounded like when the orchestra recorded the cue without that instrument. In the late ‘50s, the Electro-Theremin began to be used in films and TV shows. Easier to play than the Theremin while sounding similar, it can be heard in The Giant Gila Monster and in TV’s Lost In Space, not to mention making an appearance in The Beach Boys’ classic song, “Good Vibrations.” While the compositional and orchestrational devices used in science fiction films are generally the same as those used in other genres, there are sometimes exceptions. Flutter-tongued brass probably wouldn’t work very effectively in your standard romance or western, but it certainly has been used with great success in monster movies. Even today, when sampled and electronic sound effects are combined with music to create decidedly sci-fi-sounding scores, these scores are still very similar to those written for contemporary non-sci-fi scores. And many contemporary monster movies (Jurassic Park) still have very traditional-sounding scores. |

||||||||

|

Another difference between monster music and other film music is that the musical themes signifying the creatures are usually shorter than characters’ themes in other pictures like romances and spectacles, although there are certainly many exceptions. It would appear as if long, involved melodies don't work well with powerful, brutish monsters. These monster themes were usually played prominently by brass, although Theremin or Novachord might also carry the theme at times. King Kong's three-note motif probably started the trend in 1933. In the 1950s, many cinematic monsters had four-note themes,

starting with The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms, followed by It Came From Beneath The Sea and 20 Million Miles To Earth. Of course, four-note motives

are not the exclusive property of monsters, as Beethoven showed with his fifth symphony. While Bronislau Kaper’s ant theme from Them! was longer than four

notes, it was a far cry from one of Max Steiner’s extended romantic themes from Bette Davis pictures. While long, pretty melodies are seldom the primary themes in monster/sci-fi movies, such themes are often assigned to the love sub-plots or to the plight of those dealing with the loss and destruction caused by the killer critters. If you go back to the horror films of the 1930s and ’40s, longer melodic statements sometimes categorized those monsters. Those earlier creatures were more human, and that humanity often manifested itself in the music. A longer melodic motif seemed more appropriate to an invisible man or a werewolf than to a gigantic leech or a dinosaur running amok in a big city. And although most monster movies certainly have more brass-dominated action music, they don’t necessarily have any more than war films, swashbucklers, or other action films. What Makes Monster Music Special? One of the biggest differences between monster/sci-fi music and other film music is what makes it so special. If two people are kissing on the screen, any one of a million pretty melodies will convey the love the couple is feeling. The visual by itself is enough to make us believe they're in love, and the music can almost be superfluous. But how do you convince your audience that mole creatures are living underground with beautiful albino dancers, or that crystals from outer space have landed on Earth and are growing to gigantic proportions? The ideas and visuals can be so bizarre that conventional film music might not be enough to support the concepts, and can actually hurt the believability of the premise. Therefore, composers working on horror films sometimes have to let their imaginations run wild in order to make these concepts as plausible as possible. It takes more creativity to convince the audience that a 300 -foot mantis is an actual threat, especially when it looks like a huge, plastic puppet. Composers can definitely get a little outlandish at times and it will work in a way that the same music wouldn't fit in a more conventional drama. Irving Gertz felt that The Monolith Monsters could be characterized a certain way. Try to picture this music describing anything in a Jimmy Stewart or Henry Fonda movie. Because science fiction and horror films can push a composer’s creativity better than other genres, many composers’ best work has been done for these types of pictures, including Max Steiner's King Kong, John Williams’ The Empire Strikes Back, Bernard Herrmann’s Psycho and Mysterious Island, Miklós Rózsa’s Thief Of Baghdad, Herman Stein’s This Island Earth, Sir Arthur Bliss’s Things To Come, Franz Waxman’s The Bride Of Frankenstein, and Hans Salter’s House Of Frankenstein. |

||||||||

|

Contents of this website Copyright © 1996 - © 2024 Monstrous Movie Music. |

||||||||